Mobile Motion Film Festival released a fascinating list of “The 10 Best Self-Funded Films.” The list includes films by Orson Welles, Satyajit Ray, John Cassavetes, Richard Linklater and Peter Jackson, among others.

These were movies that the directors and producers felt passionately about, but couldn’t get Hollywood interested in funding–whether because of prohibited themes of interracial love, a radical new plot structure, or a lack of ‘favor capital’ in Hollywood–so they bent over backwards to make the films themselves.

Tiger Within is exactly this type of project. Rafal Zielinski and Gina Wendkos first started talking about making the movie 20 years ago. The message– of love and forgiveness in a world of hate — is important to both of them, and the story is honest and heart-warming. But Hollywood couldn’t seem to see past a movie whose main characters were an octogenerian and a bigoted young runaway. To make this film, they realized they will have to work outside the system. Zielinski has personally funded the bare bones budget required to start shooting, but to bring the movie to New York (where they have always dreamed of shooting it) and to add additional color, Zielinski has turned to his community. Like these ten filmmakers, Tiger Within will a project of elbow grease, sweat, love, and the grassroots belief and support of those around us.

Please contact info@filmartmovies.com if you have interest in being a part of this journey–either as an investor, a volunteer, or even donating space or materials. We are committed to the team effort self-funded films!

Here are three examples from Mobile Motion’s post, though the full list can be found here.

Orson Welle’s “Othello” (1951)

After a decade in Hollywood, Welles moved to Europe and prepared to make a film version of Shakespeare’s Othello, but the film’s Italian producer went bankrupt on the first day of shooting and the production was shut down.

After a decade in Hollywood, Welles moved to Europe and prepared to make a film version of Shakespeare’s Othello, but the film’s Italian producer went bankrupt on the first day of shooting and the production was shut down.

Not prepared to let the project fail, Welles began using his own money. When funds ran dry, he took acting roles to refill his bank account. The production had to be halted at least 3 times while Welles went off to play parts in other films, such as The Third Man. While he was away one time, the costumes for the film were impounded. Rather than wait for new costumes, Welles and his crew came up with creative ways to keep filming. Locations had to be used creatively. One fight scene starts in Morocco but the final shot was filmed in Rome, months later. You can read about this epic shoot in Micheál MacLiammóir’s book Put Money in Thy Purse (he played Iago).

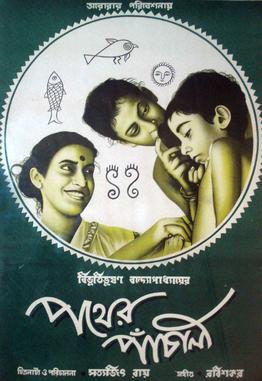

Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) – (English: Song of the Little Road)

Early in his career, before he became a renowned filmmaker, Ray was working as a graphic designer and was paid to create illustrations for Pather Panchali, a coming-of-age novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay.

Early in his career, before he became a renowned filmmaker, Ray was working as a graphic designer and was paid to create illustrations for Pather Panchali, a coming-of-age novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay.

A few years later, Ray set out to make a film adaptation. But with the film lacking stars, songs and actions scenes, nobody was prepared to provide funding.

So Ray borrowed enough money to begin filming, hoping to secure finance later. He worked without a script, using just his illustrations and a series of notes. The actors and crew were mostly nonprofessional. Even cinematographer Subrata Mitra had never before operated a movie camera. When money ran out, Ray pawned his life insurance policy and sold his collection of gramophone records. Ray’s wife, Bijoya, sold her jewels. Shooting continued in intermittent bursts over 3 years, with the West Bengal Home Publicity Department loaning the final funds which were filed under “roads development”.

On release, Pather Panchali struggled to find an audience. But word of mouth led to filled up screenings within a week or two. The film received critical acclaim, with Philip French of The Observer calling it “one of the greatest pictures ever made”.”

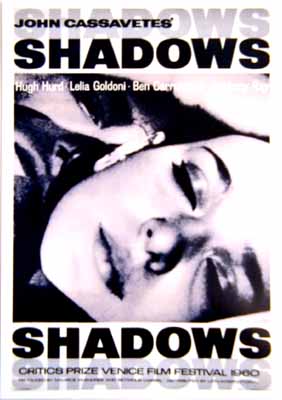

John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959)

John Cassavetes was a filmmaker considered by many to be one of the earliest pioneers of independent American cinema. Like Orson Welles, Cassavetes took lucrative acting roles to fund his films, enabling them to be made without Hollywood interference (he’s well known for appearing in films such as Rosemary’s Baby and The Dirty Dozen).

Cassavetes had been running an actor’s workshop and was on radio promoting a film he’d recently acted in. When he mentioned a storyline they’d been developing in the workshop and how they would like to film it, listeners sent him about $2000 in small amounts (over 50 years before Kickstarter was invented). Other donations came from Cassavetes’ friends. The only crew member who had any previous film experience (apart from Cassevetes) was the German cinematographer, Erich Kullmar.

With just a story outline and no script, the actors were encouraged to improvise each scene. In true Guerrilla-style, filming took place in locations they could find for free, including Cassavetes’ apartment. With no permits for the street scenes, cast and crew had to be prepared to pack up and leave at any moment. Operating the camera, Kullmar had to try to follow the actors’ improvisations and work mostly with available lighting. The result is something with a real live energy, almost documentary style, which still feels fresh today. It laid some important markers for films such as Woody Allen’s Manhattan and Scorcese’s Mean Streets (and perhaps hundreds of others).

In 1960, Shadows won the Critics Award at the Venice Film Festival and is considered by film scholars to be a major milestone in American independent cinema.”